Why relying on GPOs isn’t always the best plan: When ‘custom sourcing’ pays off

While using Group Purchasing Options (GPO) or Parent Company contracts for sourcing is better than doing nothing and it requires little effort, it’s not always the best approach as it can sacrifice 2-3%points of EBITDA margin. Understanding when ‘custom sourcing’ makes sense is the key. We offer a framework to guide this evaluation.

We sometimes encounter Private Equity partners or CFOs who tell us “We have procurement covered! We’re in a GPO“…or “We just leverage our parent company’s contracts…” Who could blame them? Seems reasonable to assume that one could do no better than to leverage such approaches and buying power. In addition, this approach requires little effort. What could be better?

It turns out, this seductively easy approach is not always better. For certain spend categories, whose attributes favor customer sourcing, the easy approach results in 8-15% higher spend versus what the company could spend following a deliberate sourcing effort. How could this be? It turns out buying power isn’t the only factor that matters…

Selecting the best sourcing approach:

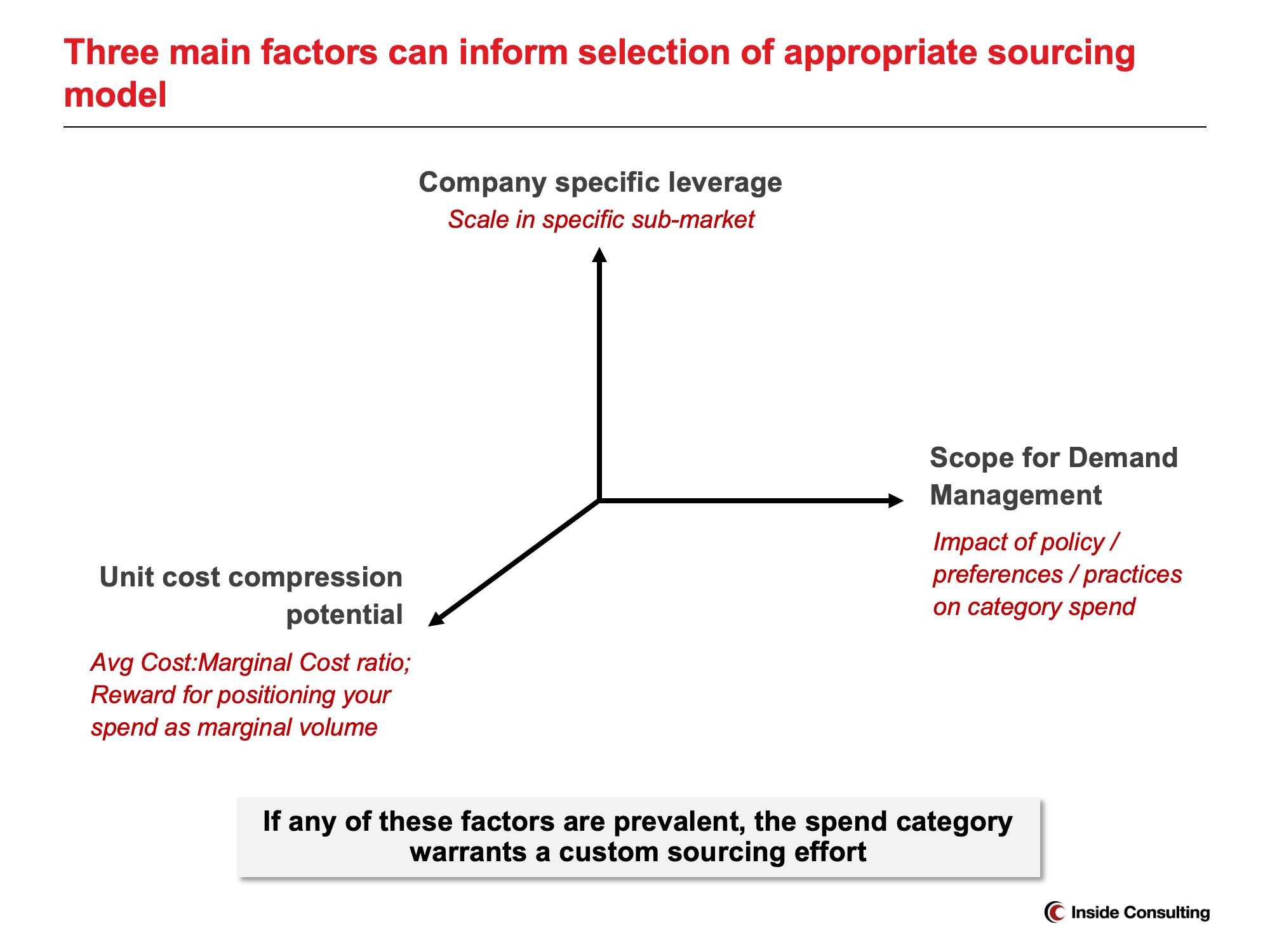

The “best” sourcing approach– i.e., either relying on GPO/ParentCo contract or conducting custom sourcing effort– depends on the degree of incremental benefit a company could obtain via custom sourcing. To select the appropriate sourcing model, we suggest companies evaluate each major spend category along three factors:

- Degree of company-specific leverage: is the firm a large/significant buyer in the specific sub-market?

- Degree of potential unit cost compression: are suppliers’ marginal costs low relative to average costs? Could the company threaten substitution?

- Degree of demand management potential: is spend highly influenced by user preferences/practices and/or company policy?

Below we explain each suggested evaluation factor and why it matters:

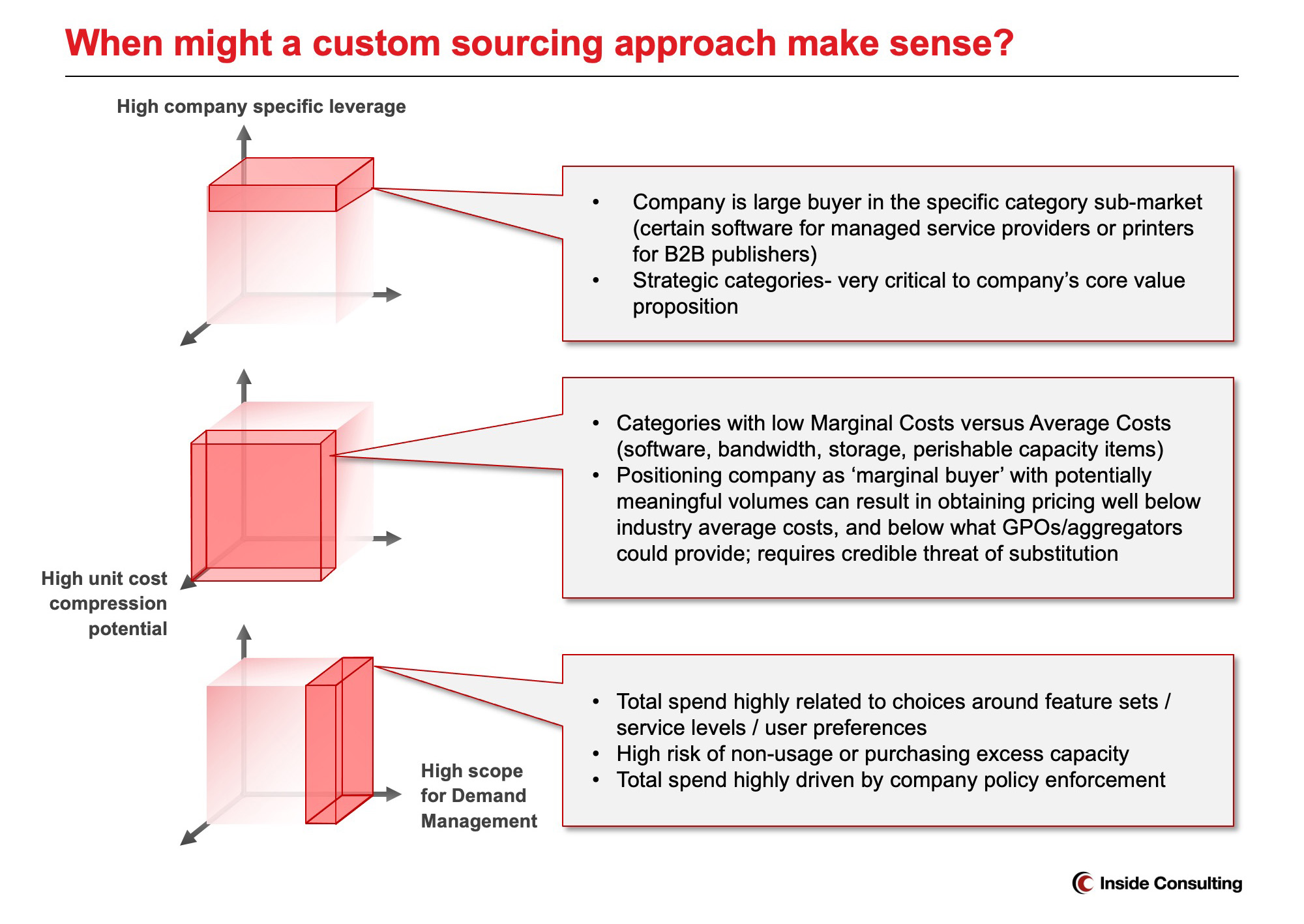

Degree of company-specific leverage: Purchasing leverage does not simply depend on absolute scale. Even mid-market companies can have a surprising degree of leverage with some suppliers if one or more conditions exists:

- The company is a relatively large-scale buyer in a specific sub-market: Given the company’s focus it’s possible that they are a big buyer who might matter a lot to the supplier. We’ve seen this situation in IT with various kinds of specialized software / services. We’ve seen this in more industrial contexts where clients have been big users of antiquated services and were key to suppliers’ capacity utilization.

- The company is especially ‘indifferent’ or able to switch: Suppliers count on some degree of dependence (“lock-in”) to increase their margins. It is possible to invest in systems / processes / people such that one’s company would be able to switch providers more readily than most other customers. If this is really the case for a company, this is powerful information and it changes the pricing decision-making for the supplier. The company’s business truly becomes “marginal volume” that could stay or go, therefore warranting “marginal cost pricing”. The average buyer gets only “average cost pricing”.

Degree of potential unit cost compression: The greater the difference between “marginal cost” and “average cost”, the greater the potential savings from a company being viewed as marginal volume. High fixed-cost suppliers such as Technology (e.g., software), Telecom (e.g., bandwidth), or Manufacturing (e.g., printing) typically have very low marginal costs. Perishable capacity items also exhibit this relationship.

The key is demonstrating a credible threat of substitution.

Degree of demand management potential: To the extent category spend depends significantly on company’s variable consumption or preferences on service levels, there can be significant savings (or over-spending) driven by demand management. Consider a few examples:

- T&E policy: Many companies use GPO rates for hotels/rental cars/etc. Setting aside the fact that custom negotiations with hotels can bring better rates, the key question is really ‘how much should staff be traveling at all?’ – which really hinges on meeting planning discipline. T&E spend is really much more about volume management, not unit pricing.

- Printer settings: the ratio of color printing to black&white (B&W) is a major cost driver- with color costing roughly 10X that of B&W. Thoughtful discipline around print settings can affect print spend much more than incremental unit price differences.

- Enterprise Software: There are two main demand management issues at play: 1) license utilization and 2) version/module necessity. Some company procurement departments benchmark ‘per license’ pricing diligently, only to overspend via unused licenses and/or optional modules that are not truly needed. Only a holistic analysis of each spend area with its unit cost and volume drivers can assure a company that their spend is well-managed.

We’ve seen that in some cases when a company assumes that their spend for a given category is optimized because they believe their pricing to be ‘best in class.’ This assumption can then lead to reduced diligence on demand management. Just a slight amount of overbuying can offset even the best unit pricing. For categories where demand management is critical to overall spend management, high-performing companies understand spend drivers and have collected key data already, making custom sourcing very low incremental effort. The A+ answer would be to conduct periodic ‘zero-based’ budgeting and assess just what volume, for which spec/service level, is truly needed– but in our experience, only the companies that conduct custom sourcing go to this length; the companies who rely on GPO or ParentCo contracts effectively assume demand management away and end up overspending.

What’s it worth? The incremental benefits from ‘custom sourcing’

You might see all this and nonetheless still wonder “but how could it be that a midsize company could receive better pricing than their large ParentCo or a GPO?” Think it through: Suppliers can rationally offer pretty good pricing to these types of buyers that is still above ‘marginal cost.’

Over the course of our 16-year firm history (dating back to 2005) we’ve secured pricing across various categories often 8-15% lower than what the client was paying via their GPO or their Parent Company contract. Typically, these clients had to sign Non-Disclosure Agreements to prevent the news of their deal from spreading. The point being: don’t assume your GPO rates are necessarily best in class.

Concluding thoughts:

- Don’t assume your GPO rates are necessarily best in class; consider where custom sourcing might make sense. You might be surprised how much savings are available.

- Beware the loss of rigor that can result from taking the easy approach.